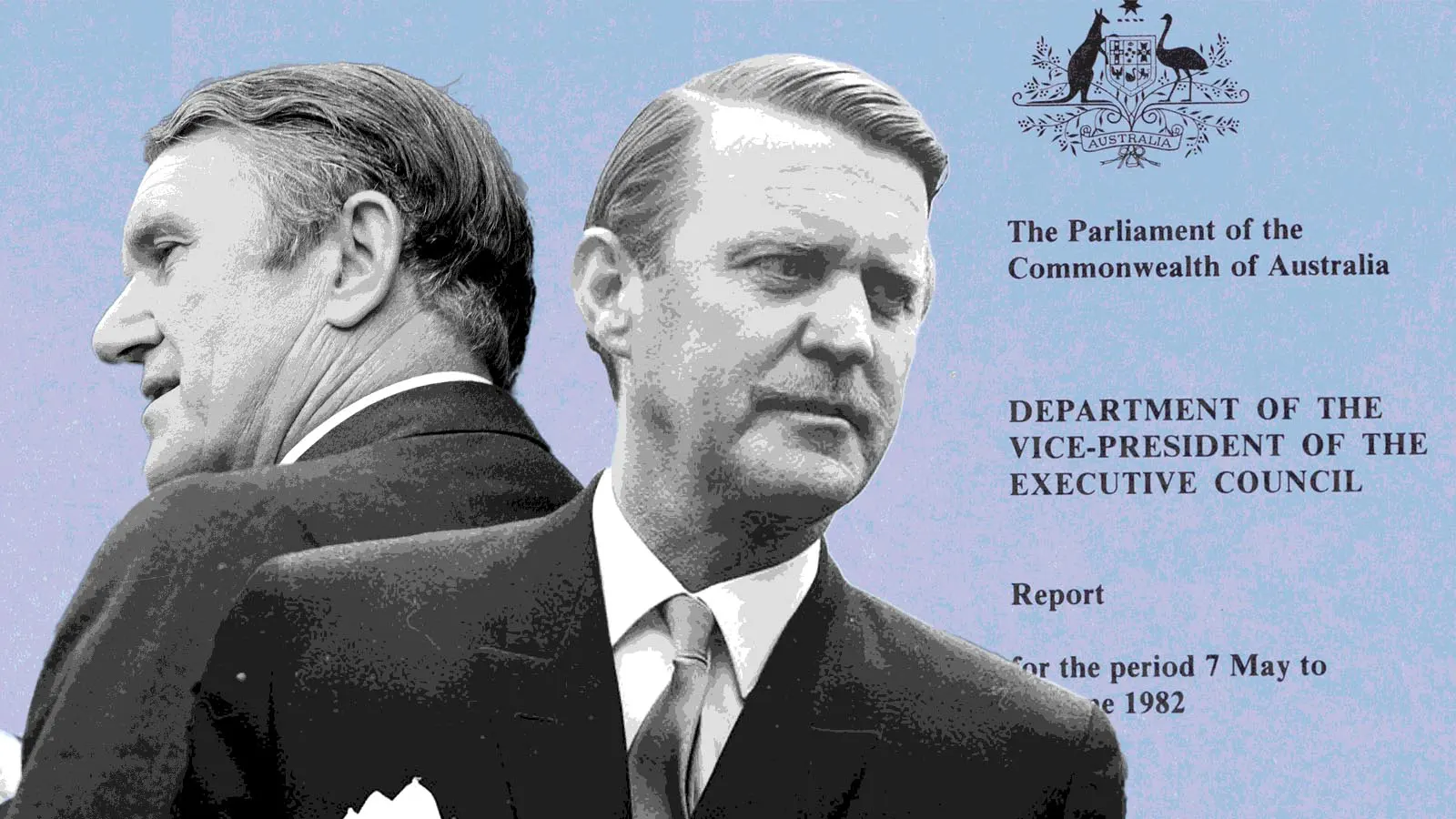

About that time Malcolm Fraser created a fake department

With the controversy erupting earlier this year over Scott Morrison’s decision to keep embattled ministers Christian Porter and Linda Reynolds in his cabinet, it may be worth remembering how much worse it could have been had the Prime Minister not been able to find “real” jobs for Porter and Reynolds. He could have, as Malcolm Fraser did in 1982, created a fake department for one of them to lead.

To understand how and why Malcolm Fraser did this, you first need to know about the Executive Council.

The Executive Council is the body, established by section 62 of the Constitution, through which government Ministers formally advise the Governor-General to exercise their power. Its membership consists of current and former federal Ministers, though only current Ministers are summoned to the meetings. When you see a law saying that the “Governor-General in Council” has the power to do something, that’s the Council being referred to.

The Vice-President of the Executive Council is the minister in the government who convenes the Council when the Governor-General is not or cannot be present. The role is effectively a sinecure: a ministerial position with very few actual responsibilities other than occasionally standing in for the Governor-General at a meeting to rubber stamp decisions already made by the Cabinet.1 Not exactly the strongest candidate for the creation of a new department.

When he created the Department of the Vice-President of the Executive Council in May 1982, Malcolm Fraser admitted that it would not have many responsibilities and that its establishment was purely functional:

The new Department of the Vice-President of the Executive Council is a vehicle for the appointment of a senior minister whose functions can be performed without involving heavy departmental responsibilities.2

It served no purpose except to allow Leader of the House and outgoing Defence Minister Sir Jim Killen to remain in Cabinet and alleviate any potential question as to the validity of appointing a minister without portfolio. All, of course, while retaining Killen’s significant ministerial salary. An earlier incarnation of the department also briefly existed under the McMahon government but, unlike the Fraser-era department, it was relatively uncontroversial and was given responsibility for indigenous affairs and a small number of agencies.

It was characterised by the press at the time as “$74,000 just to avoid a by-election”, as it was thought that Killen would have left parliament and caused a potentially damaging by-election had he not received a ministry. The department was not assigned any legislation to administer under the Administrative Arrangements Order creating the department.

The appointment was controversial from the start, pilloried by the Labor opposition as desperate. At the tabling of the Department’s diminutive annual report, Labor Senator for Tasmania Nick Bolkus lashed the lack of any apparent functions of the department, questioning whether Killen merely served as a “typist or a clerk […] sending out notices [for] meetings of the Executive Council”.3 The report revealed that, in the first few months of its existence, the department had only spent (after adjustment for inflation) about $7,500 to hire two staff. Bolkus quipped that the report likely cost more to produce than the department’s operations.

The controversy over the appointment led Fraser to insist in an interview with The Canberra Times that Mr Killen would “not infrequently” act for other ministers when they went overseas and to point out that “[it’s] not uncommon in British Parliaments to have ministers without portfolio for the reasons [he] advanced in relation to Mr Killen”. It appears that Killen acted for a minister in this capacity only once, as mentioned in the interview, acting in deputy prime minister Doug Anthony’s trade portfolio when Anthony went overseas.

Before 1951, it was common for people to hold the officer of Vice-President without another portfolio, the last of these being Dame Enid Lyons (pictured above) who believed that she, the first woman in Cabinet, was only appointed because “[the men in Cabinet] only wanted me to pour the tea”. At least ten people have been explicitly appointed as ministers without portfolio, including Stanley Bruce though, given his responsibility as “second in charge for every Commonwealth department” and as High Commissioner to Britain, his title was perhaps a misnomer.

By the 1980s, there were legal concerns, arising from the text of section 64 of the Constitution, that appointing a minister without portfolio may be unconstitutional. Section 64 says that the Governor-General may “appoint officers to administer such departments of State […] as the Governor-General in Council may establish”. It does not appear to make provision for a Minister appointed to administer no department.

Ironically, the structure of the Department created to avoid the legal question of whether a Minister has to actually administer a department created other legal questions. Fraser appointed his own departmental secretary, Geoffrey Yeend, to a “dual appointment” covering both PM&C and the VPEC department, without a clear legal basis. Yeend was only actually appointed as the acting secretary of VPEC. This potential problem was resolved later in the year with an amendment to the Public Service Act explicitly allowing dual appointments, though it does not appear that Yeend was ever formally appointed Secretary on a permanent basis before the VPEC department was abolished.

Bob Hawke abolished the department on coming into office in 1983 when he appointed his Special Minister of State Mick Young to the role. Since 2015, the Vice-Presidency is usually held by the Leader of the Government in the Senate, currently Simon Birmingham. Although Scott Morrison may have shamefully resurrected Porter and Reynolds’ otherwise destroyed ministerial careers, he thankfully did not choose to resurrect Malcolm Fraser’s fake department.

The header image was created from a photograph licenced as Creative Commons BY 4.0 by the State Library of NSW and the SEARCH Foundation, a page from a document from the National Library of Australia, as well as a photograph from the National Archives of Australia.

-

Strictly speaking, the Vice-President doesn’t have the power to sign off on documents. Documents are “presented to the Governor-General for approval as soon as possible after the meeting”. (Executive Council Handbook). ↩︎

-

M Fraser. 1982. “Ministry and Departmental Changes”: page 6. ↩︎